Why Muscle Glycogen — Not Calories — Limits Endurance Performance

Endurance athletes are constantly told to “eat enough carbohydrates.” While that advice is broadly correct, it misses a more important question: where those carbohydrates are stored.

A 2025 meta-analysis published in the Journal of Applied Physiology brings this distinction into focus. Looking across more than 30 controlled endurance studies, the authors showed that consuming carbohydrates during long exercise slows the depletion of muscle glycogen. The effect is not dramatic — but it is consistent, and it matters because muscle glycogen is a uniquely limiting fuel source.

Two Glycogen Stores, Two Very Different Roles

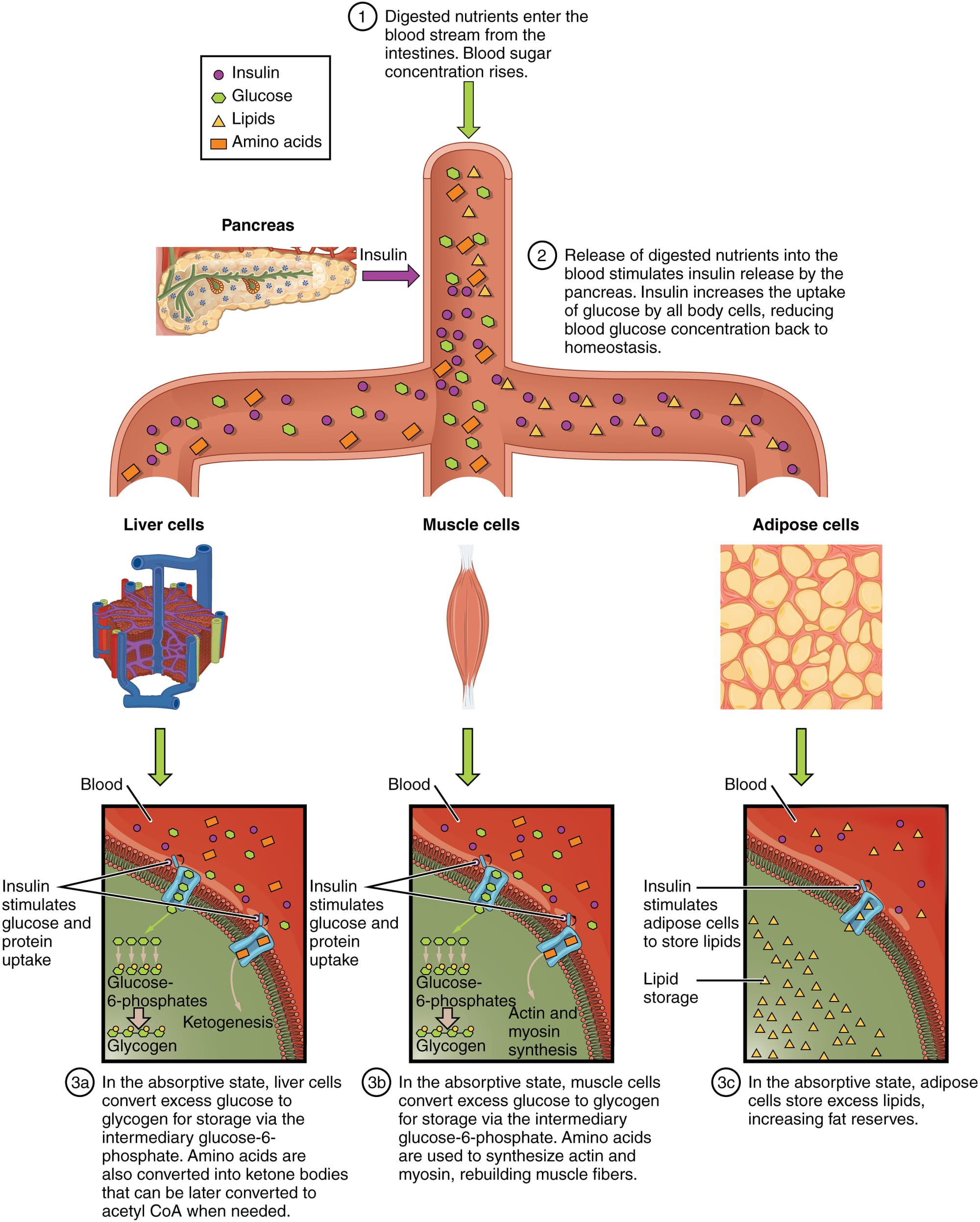

Your body stores carbohydrates as glycogen in two main places. Liver glycogen acts as a regulator: it stabilizes blood sugar and keeps the brain supplied with glucose. When liver glycogen drops, you may feel light-headed or unfocused, but your muscles can often keep working.

Muscle glycogen is different. It is stored directly inside muscle fibers and can only be used by the muscle in which it sits. It cannot be shared with other muscles, and it cannot be meaningfully replenished while you are exercising.

That local, closed-system nature is what makes muscle glycogen special — and unforgiving. Once it drops too low, force production declines and pace becomes unsustainable, even if you are still taking in carbohydrates and your blood sugar looks fine.

What the New Evidence Actually Shows

The meta-analysis examined endurance bouts typically lasting 90–120 minutes. Across studies, athletes who consumed carbohydrates during exercise consistently used less muscle glycogen than those who did not. On average, about 20–25 mmol/kg of muscle glycogen was spared.

In practical terms, carbohydrates during exercise do not stop muscles from using glycogen. Instead, they slow the rate at which a limited, muscle-local fuel reserve is drained.

Why This Shows Up as “Dead Legs”

At low intensities, fat can cover much of the energy demand. But as soon as intensity rises — marathon pace, long climbs, sustained tempo — muscle glycogen becomes essential. When it declines, effort increases disproportionately.

This effect is amplified by muscle fiber recruitment. Fast-twitch fibers, which are increasingly used late in races, on hills, or during surges, store less glycogen and burn it faster. As glycogen drops, the body is forced to recruit less efficient fibers sooner, making the same pace feel harder and harder.

This is why endurance fatigue often presents as heavy legs and failing form, not hunger or dizziness.

What Fueling During Exercise Really Does

Carbohydrates consumed during exercise provide an external glucose supply to working muscles. This reduces the need to rely exclusively on internal glycogen stores and preserves muscle function later in the session.

The benefit becomes most noticeable:

- In the second half of long runs or rides

- At moderate to high intensity

- When maintaining pace and technique matters most

Fueling is not about instant energy or avoiding hunger. It is about protecting a finite physiological resource.

What This Means for Everyday Endurance Athletes

For sessions lasting longer than about 90 minutes, fueling during training is not optional if performance is the goal. A practical starting point is 30–60 g of carbohydrates per hour, adjusted for intensity and tolerance.

The objective is not to replace every calorie burned. It is to slow muscle glycogen depletion, allowing you to hold pace, form, and decision-making deeper into the session.

Recovery still matters, too. Muscle glycogen refills slowly and requires carbohydrates after training — often 24 to 48 hours for full restoration after hard or long efforts.

The Bottom Line

Muscle glycogen is local, finite, slow to refill, and irreplaceable at endurance race intensity. The latest research reinforces a simple but often misunderstood truth:

Fueling during endurance exercise works because it protects muscle glycogen —the true limiter of sustained performance.

For endurance athletes, better fueling is not about eating more. It is about understanding muscle physiology — and fueling at the right time, for the right reason.

Write an easy to understand blog based on this source. Be specific what it means for the everyday endurance athlete.

Referenced publication:

https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00861.2025